Rice Winery Boksoon can be reached in a 20-minute drive from the Ulsan KTX station. A single-story long rectangular black building stands behind a small countryside bus station and a large tree. Makgeolli (traditional Korean rice wine) winery is one of the facilities that have faded away in recent years, faced with rapid industrialization and Westernized dietary lifestyles. Visiting a winery for the very first time, the function and scenery of the building was somewhat strange and unfamiliar.

To the architect Kim Minkyu, the eldest son of the winery owner’s family, the design of Rice Winery Boksoon is an extension of the family rice wine business. He named the process of dredging up his childhood memories and seeing them materialize before his eyes as ‘Fermentation Architecture’. People say architecture is the container of life. Biochemist Louis Pasteur defined Fermentation is the ‘life of the microorganism in an oxygenless environment’. We can define the primary character of Fermentation architecture as the ‘architecture that contains the life of microorganisms’. From a narrower perspective, the meaning of Fermentation Architecture may be distorted or denounced. Fermentation Architecture serves as the starting point of a discussion, as well as an architectural frame that observes the process of the chemical transformation of fermentation of the exposed organic matter.

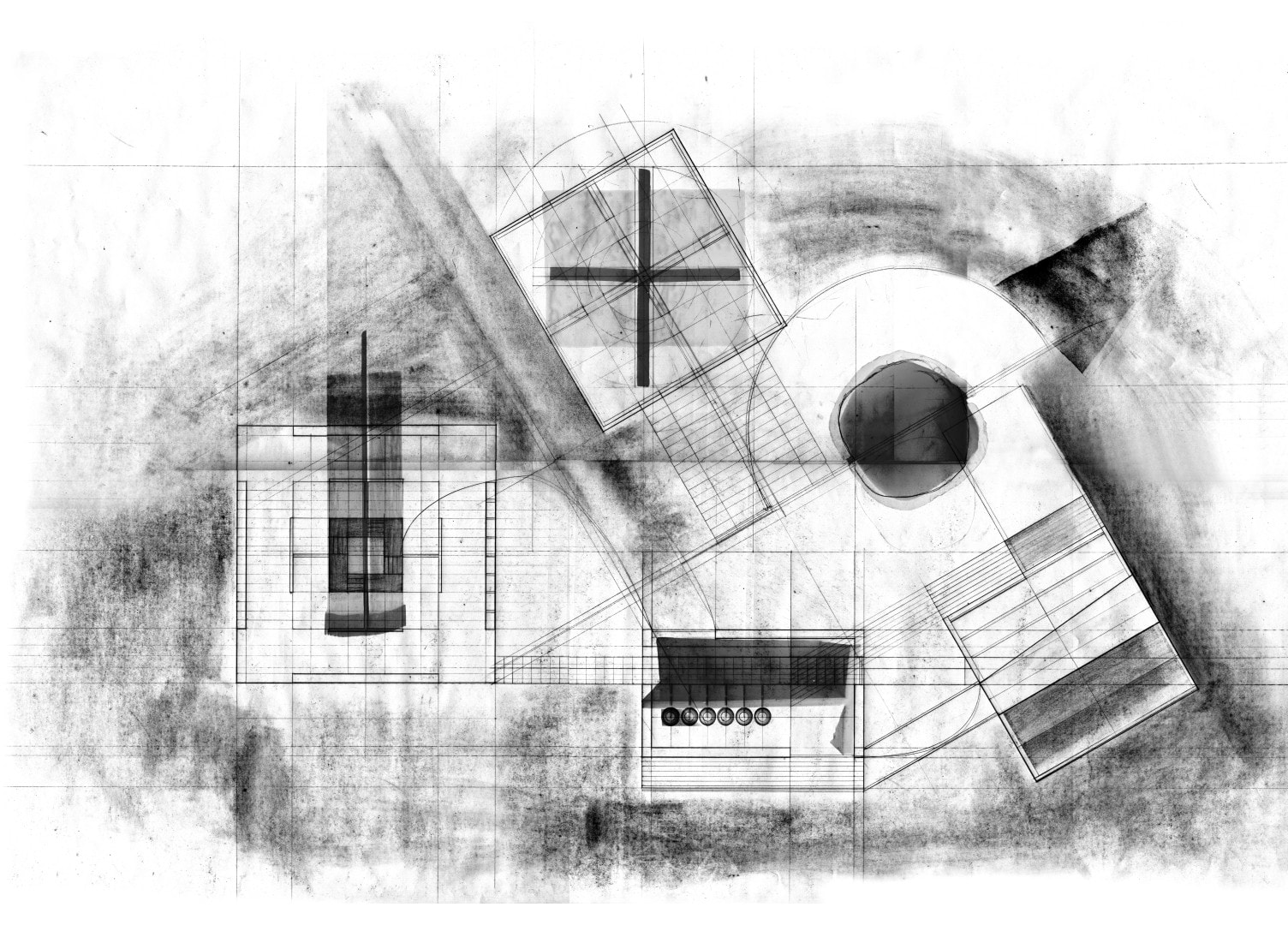

The winery, which sits at the lowest part of the paddy rice field, permeates the surrounding scenery with the old granary. It is a cultural landscape, formed by the land and its people, climate, and agriculture. Winery acts as a cultural object containing the local characteristic, which can be considered as a vernacular architecture. One can confirm that this definition is right by looking at the building process of the architecture. The building labourers who worked on the site were not professional construction workers, but local residents. One day, people left their shovels behind and went home, after they had a conflict. The construction period got longer and longer. The process where the architect had to deal with local laborers—some of whom he even used to call uncle during his childhood—is one of the characters of vernacular architecture, which is also the process of ‘architecture without an architect’.

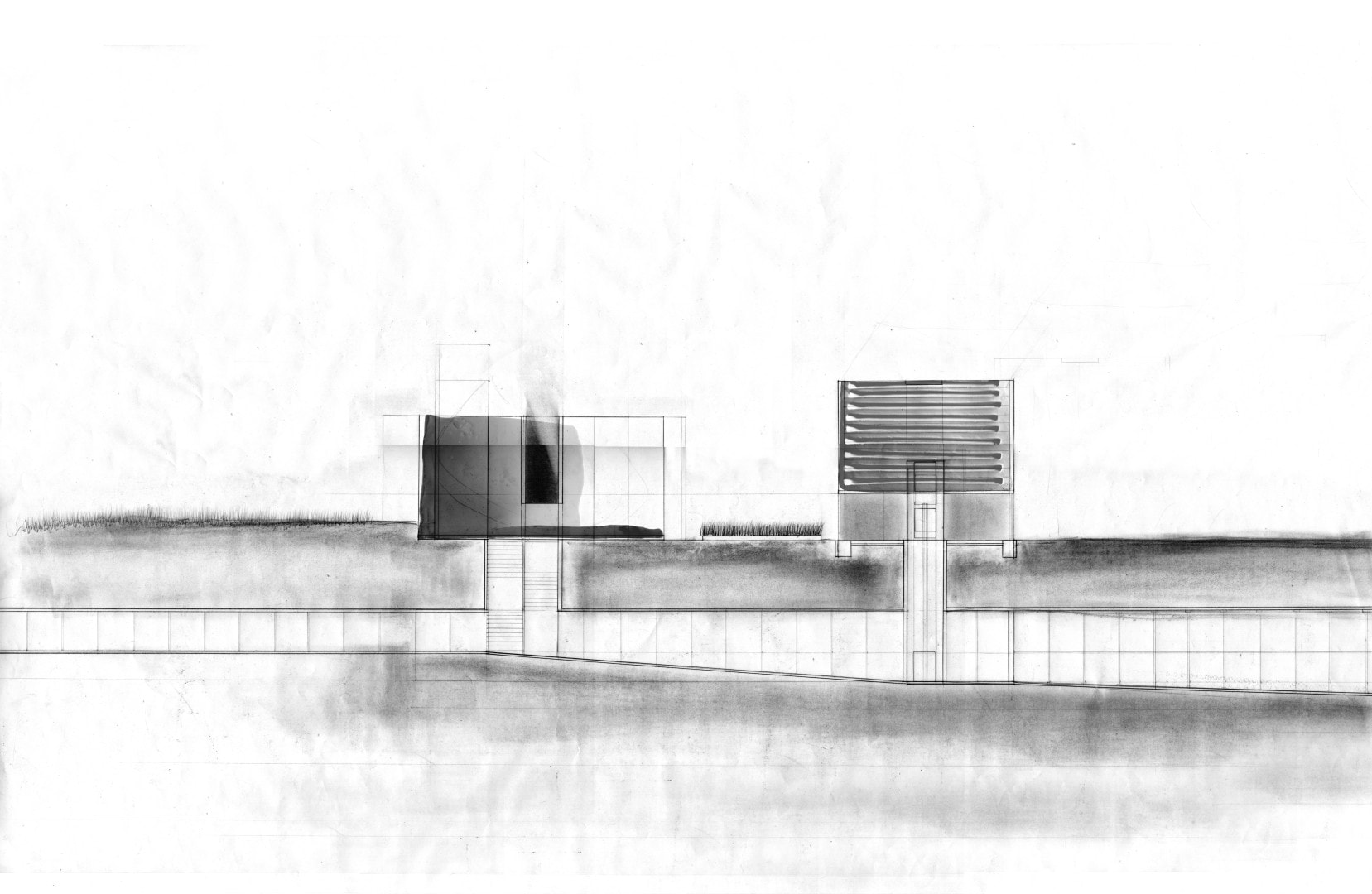

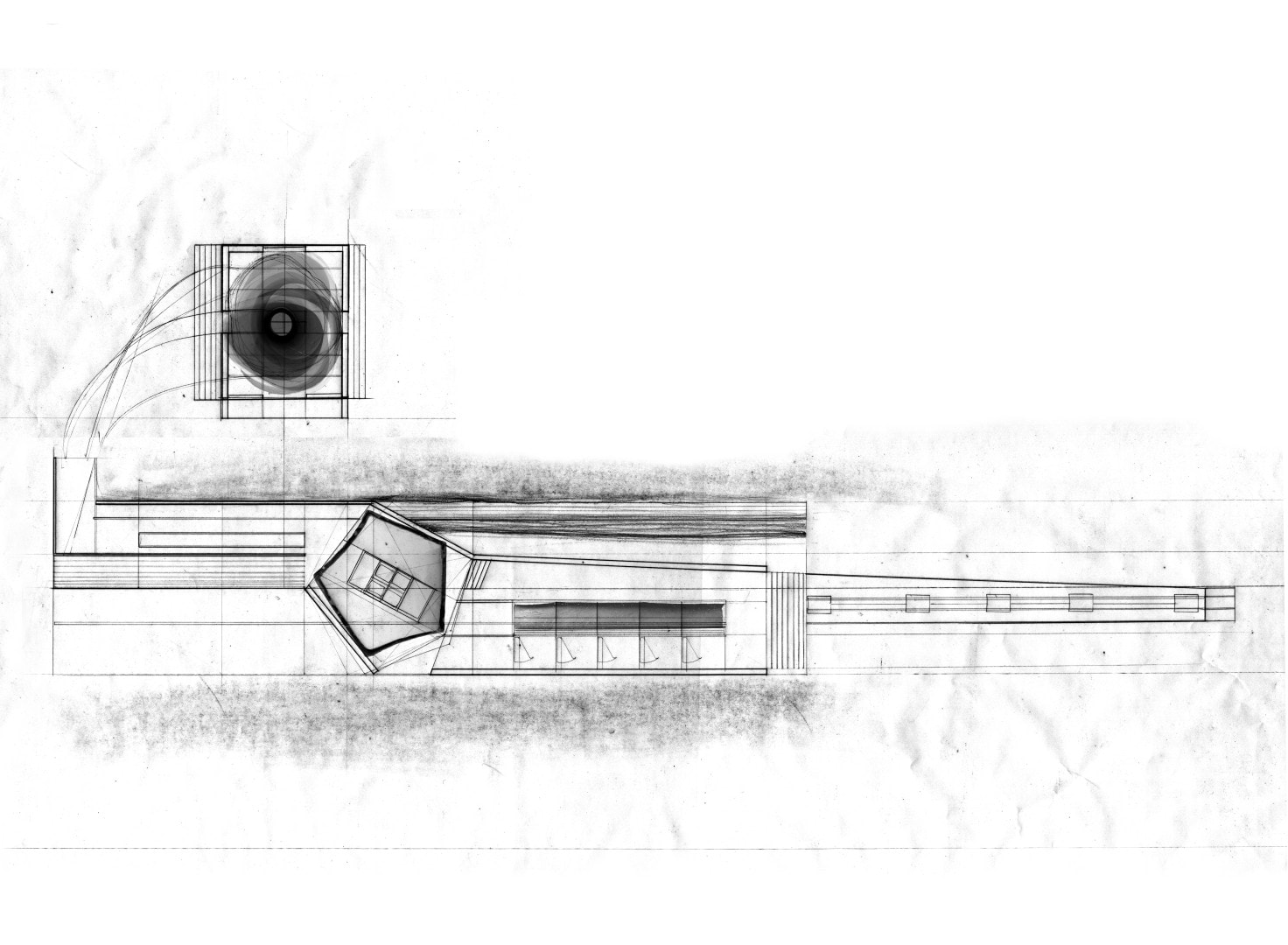

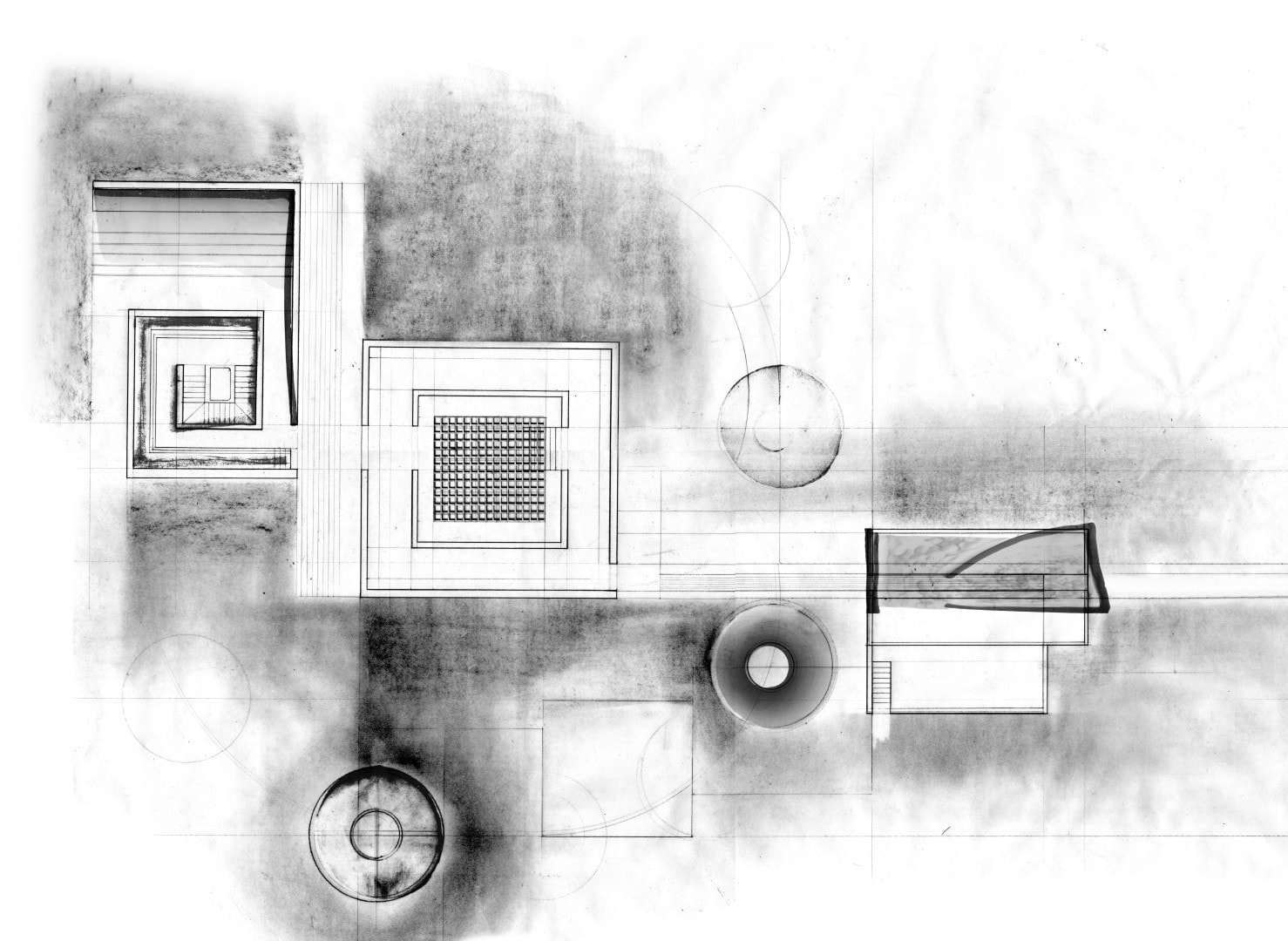

The low rectangular winery building has a partial opening at the sides. The Machia, traditional Japanese houses with narrow facades and an elongated form, has a courtyard for lighting and ventilation. Unlike the vertical openings in the Machia, the winery has horizontal openings. Attempts to overcome the monotony of the horizontal planes while fulfilling the functional needs of lighting and ventilation can be found. The wall of the building coloured with ashes from burning leftover rice straw, which gave its carbon colour. It creates a visual contrast from the ivory color of the rice wine, which is fermented inside the building. This method seems like a representation of the primitive cultivation of a burnt field, which brings rice back to the ground after it has served its purpose. The wall coloured with ashes contains meaning of transformation and circulation, which gradually takes place through time.

There is a horizontal crack on the wall. A piece of straw rope can be found inside the crack. The rope resembles the double helix structure of DNA. Not only does it resemble this form, but it contains every element of environmental information through the growth and the harvest and all the mutual relationship between the farmer and the land. This reflects the intention of the architect, which is to reveal the relationship between the land and the winery by burying the rope in the wall.

The buried rope will gradually decompose and disappear. It is how organic matter adapts to the flow of time. One can find another method inside the building, which is a large white wall that crosses through the interior of the winery. This wall, which acts as an exterior wall and the insulation of the low temperature warehouse, has yeast applied into it. Over time, mould stains will start to appear on the white wall. Mould is useful for humans. Interestingly, the fermentation of the yeast is also a biochemical process like the decomposition of the straw rope. The winery is materializing an architecture that adapts time, through its interior and exterior walls.

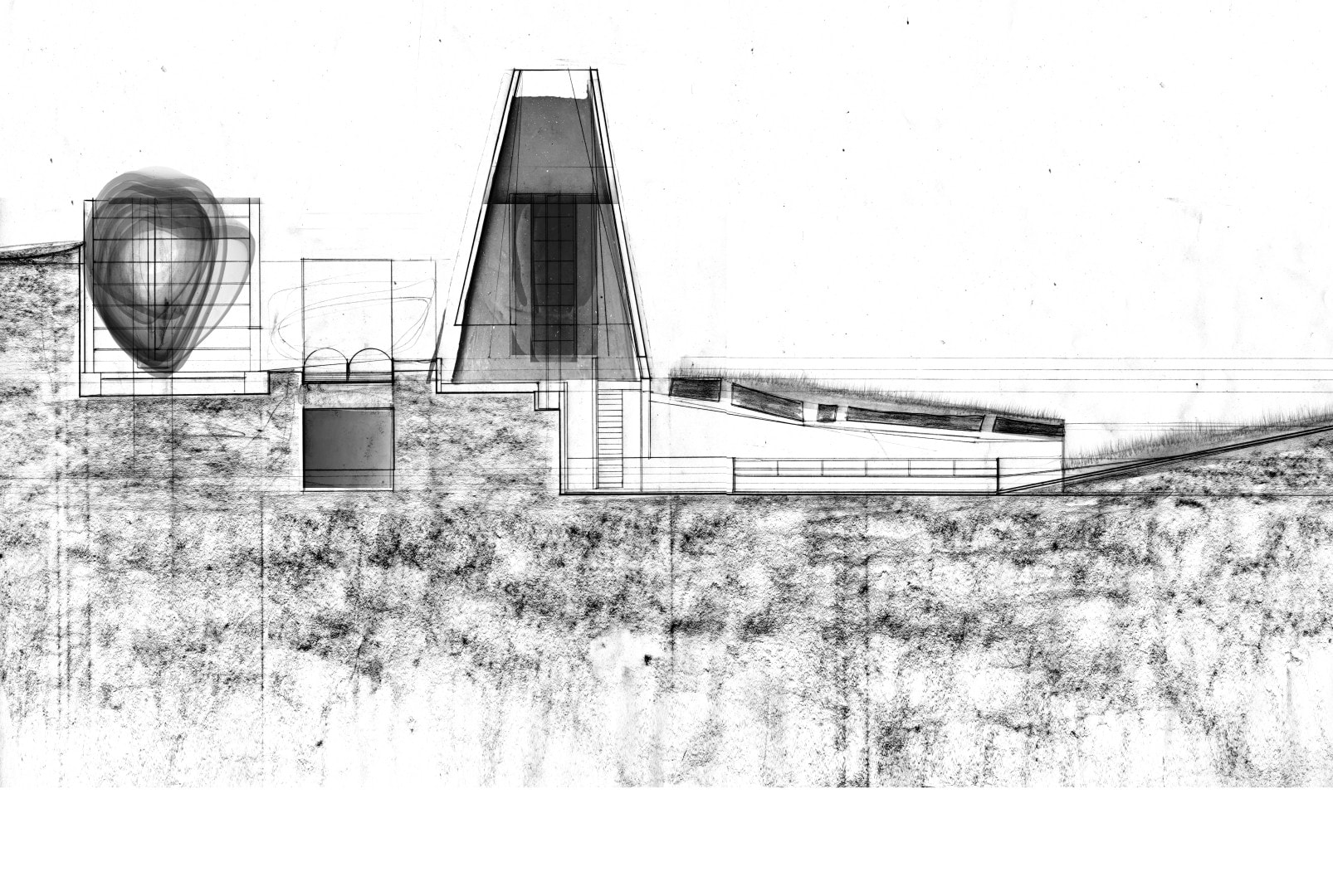

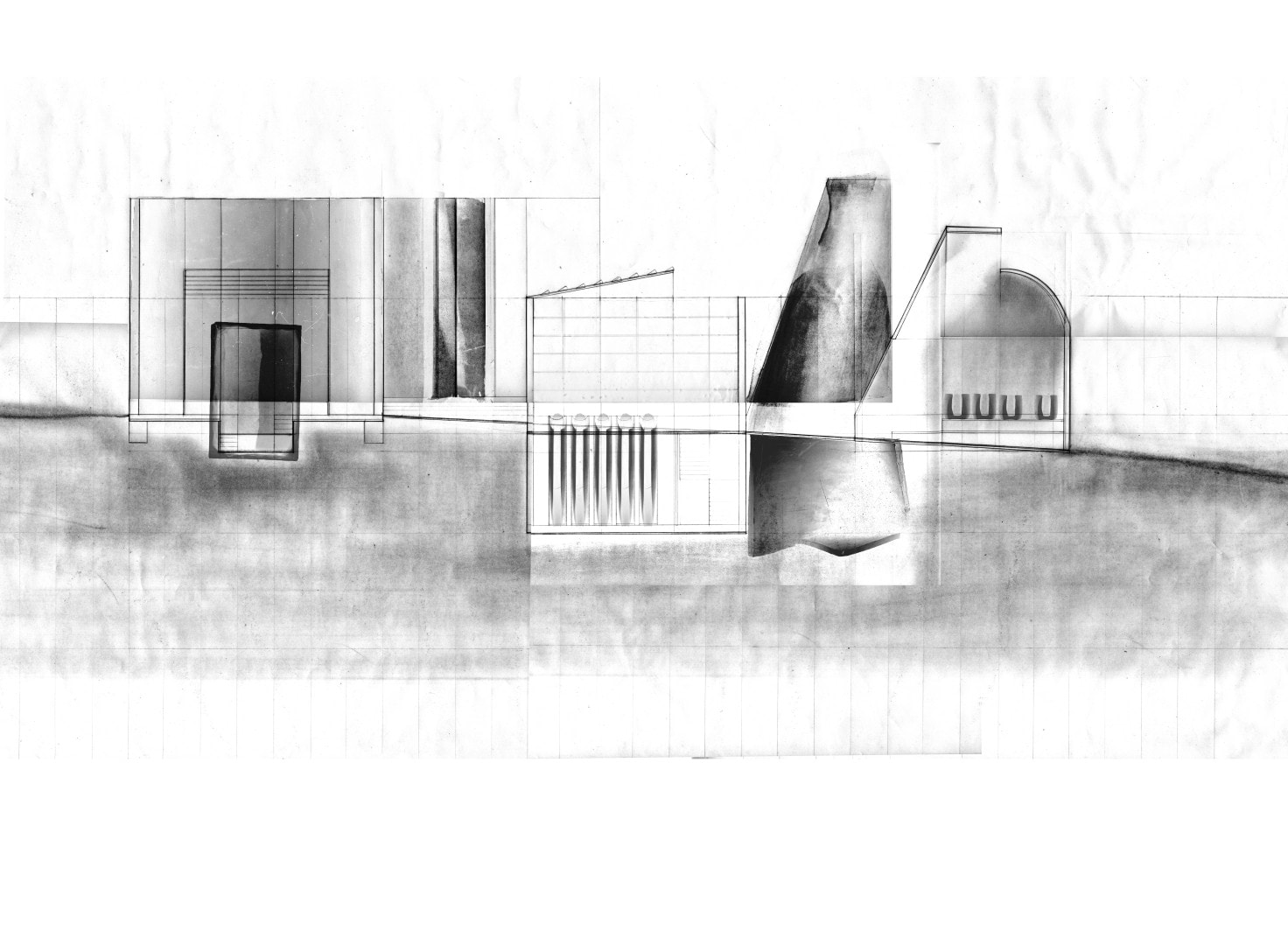

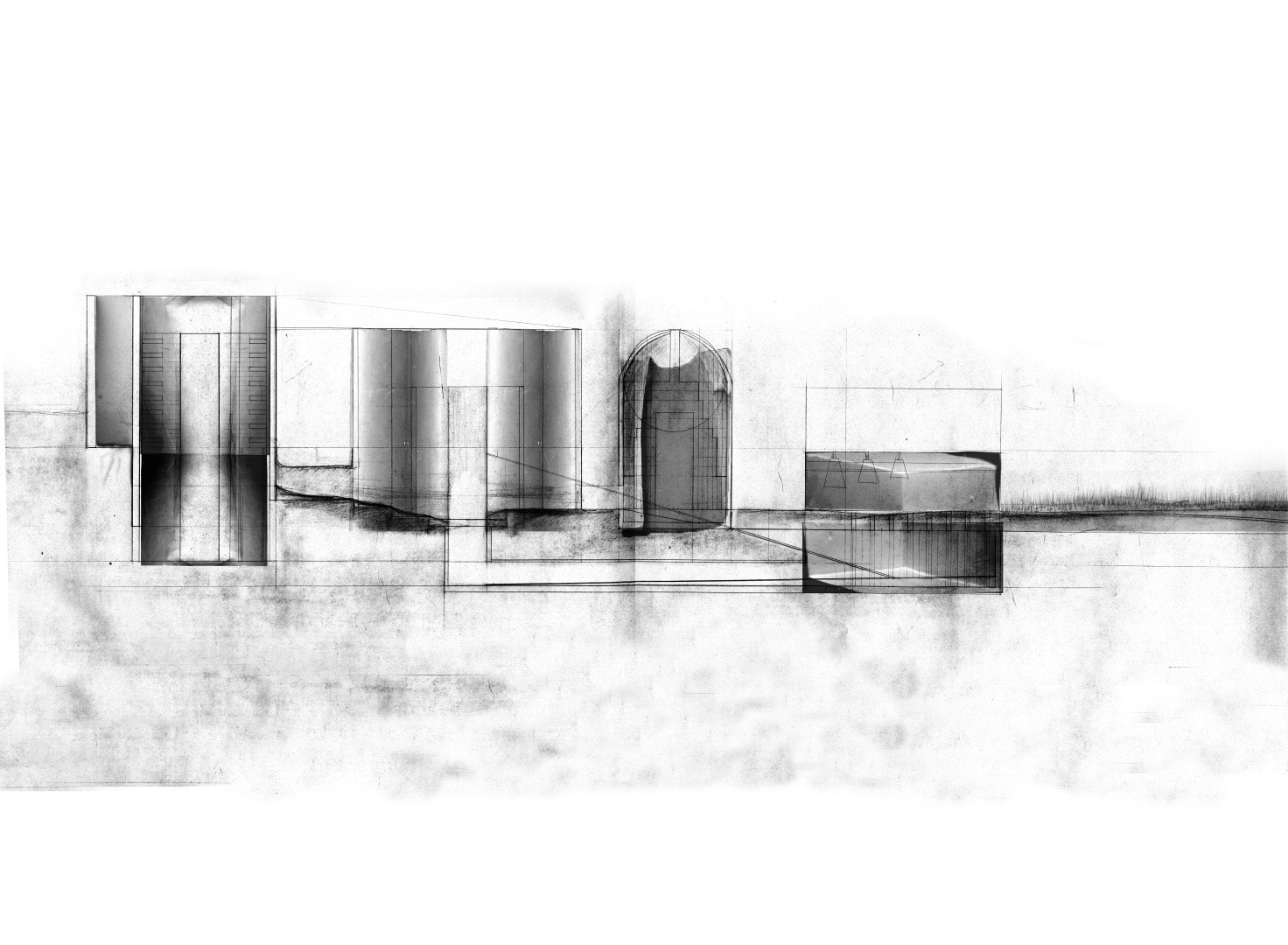

The architect is designing another work of architecture, which will cultivate yeast. The work will approach even closer the notion of biochemical transformation and its origin. It will be a process of developing Fermentation Architecture deeper, and also an opportunity for the architect to break out of his own shell. The Fermentation Architecture, which has only just begun, now makes us look forward to its evolutionary development in the future.

graduated architectural engineering of Yeungnam University and majored architecture and environmental engineering in Kyoto Unviersity. He has worked as a reserch fellow in Busan Development Institute about urban regeneration and town planning researches. Recently, he participates in the Busan Urban School Organization.

KTX울산역에서 차로 20분 정도 달리다 보면 복순도가에 다다른다. 작은 시골 버스 정류장과 아름드리나무를 앞에 두고 검고 긴 장방형의 단층 건물이 서 있다. 막걸리 도가는 급속하게 진행된 산업화와 서구화된 식생활 습관 등의 변화로 우리의 시야에서 멀어졌던 산업시설이다. 그래서인지 막걸리 도가를 둘러본 것이 처음이었던 나에게 그 기능과 공간은 아주 생경한 것이었다.

건축가 김민규에게 복순도가의 설계는 술을 빚는 가업의 연장선에 있다. 유년기에 침잠되어 있던 기억들을 하나하나 꺼내어 실존으로서 구현하는 과정을 그는 ‘발효건축(醱酵建築)’이라 명명하였다. 흔히들 건축은 삶을 담는 그릇이라 한다. 생화학자인 파스퇴르는 “발효는 산소가 없는 상태에서 이루어지는 미생물의 생활”이라고 규정하였다. 이 둘을 정합하면 ‘미생물의 생활을 담는 건축’이라는 의미로 발효건축의 일차적 특성을 정의할 수 있다. 협의로만 본다면 발효건축의 의미는 왜곡되거나 폄하될 수 있다. 발효건축이란 농경이 이루어지는 대지 위에서 자연환경에 그대로 노출된 유기물이 성장하는 생물학적 변화와 발효라는 화학적 변화를 거치는 과정을 바라보는 건축적 프레임이자 담론의 출발점이다.

계단처럼 층층이 쌓여진 논의 가장 낮은 위치에 지어진 도가는 근처에 있는 오래된 곡물창고와 함께 주변 풍경 속에 스며들 듯 자리 잡고 있다. 대지와 사람, 풍토와 기후, 그리고 농경이 만들어낸 하나의 생활문화 경관이다. 도가는 하나의 생활문화적 개체로서 지역적 고유성을 내포하고 있다. 바로 버네큘러 건축이다. 건물이 지어진 과정을 살펴보면 이 규정이 틀리지 않는다는 것을 재확인할 수 있다. 복순도가의 시공 과정에 참여한 현장 인부들은 건축 전문 기술인력이 아니라 동네주민이다. 시공 도중에 의견 차이가 발생하면 들고 있던 삽을 놓고 그냥 집으로 돌아가는 일도 있었다. 공사 기간은 기약 없이 늘어졌다. 지역에서 나고 자란 건축가가 동네 아저씨이고 삼촌이라 부르던 사람들과의 갈등을 조절하면서 진행한 건축 과정은 버네큘러 건축의 특성인 공동체적 건축이자 ‘건축가 없는 건축’의 과정이기도 하다.

낮고 긴 장방형의 도가 건물은 측면의 일부분이 앞뒤로 열려 있다. 전면부가 좁고 긴 형태의 일본 전통 가옥인 마치야(町家)는 채광과 통풍을 위해서 집 중간에 중정을 둔다. 마치야에서 상하로 열려 있는 공간이 도가에서는 측면으로 열려 있다. 측면의 단조로움을 극복하고 주택과는 다른 채광과 통풍에 대한 기능적 요구를 만족시키기 위해 고심한 흔적이 배어 있다. 도가의 검은 벽은 추수한 후 남은 볏짚을 태워서 만들어진 재를 착색시켜 만들어 먹색에 가깝다. 도가 안에서 발효되는 막걸리의 미색과 비가시적 대비를 이룬다. 그 효용을 다한 벼가 땅으로 되돌아가는 원시적인 농법인 화경의 재현 같다. 볏짚을 태운 재로 착색한 벽은 시간 속에서 이루어지는 변화와 순환의 유의미성을 담고 있다.

다시 벽을 바라보았다. 세로로 길게 벌어진 금이 눈에 띈다. 가까이서 보니 갈라진 사이로 새끼줄이 보인다. 새끼줄은 유전정보를 가지고 있는 DNA 이중나선구조를 닮았다. 단순히 형태상의 유사성뿐 아니라, 새끼줄에는 볍씨가 파종된 후 수확이 되는 시점까지의 모든 환경적 정보와 농부와 대지 사이에 이루어진 상호관계적 정보가 포함되어 있다. 새끼줄을 벽에 매립해 대지와 도가의 건축적 관계성을 이어줄 매개체를 보이지 않게 나타내고자 한 건축가의 의도를 짐작하게 한다.

매립된 새끼줄은 시간이 흐름에 따라 부패하고 소멸한다. 유기물이 시간에 순응하는 방식 중에 하나다. 도가 내부에서는 또 다른 방식을 보여준다. 건물 안으로 들어서면 도가 내부를 가로지르는 거대한 미백색의 벽을 마주하게 된다. 저온 창고의 외벽이자 단열의 역할을 하는 이 벽엔 누룩을 도포했다. 시간이 흐르면 벽체에 하얀 곰팡이가 피어난다. 그것은 인간에게 유익하다. 흥미롭게도 누룩의 발효는 인간에게 무익한 새끼줄의 부패와 같은 생화학적 과정이란 점이다. 도가는 내·외부의 벽이라는 구조체를 통해서 시간에 순응하는 건축이 되고자 한다.

건축가는 최근 효모를 배양하는 건축물을 구상하고 있다. 발효라는 생화학적 변화와 그 근원에 더 다가서는 작업이 될 것이다. 이는 발효건축을 심화하고 발전시키는 과정이자 건축가로서도 또 하나의 껍질을 탈피하는 계기가 될 것이다. 이제 시작된 건축가의 발효건축은 현재의 완결성보다 이후 전개될 진화론적 발전을 기대하게 한다.

글쓴이 한승우